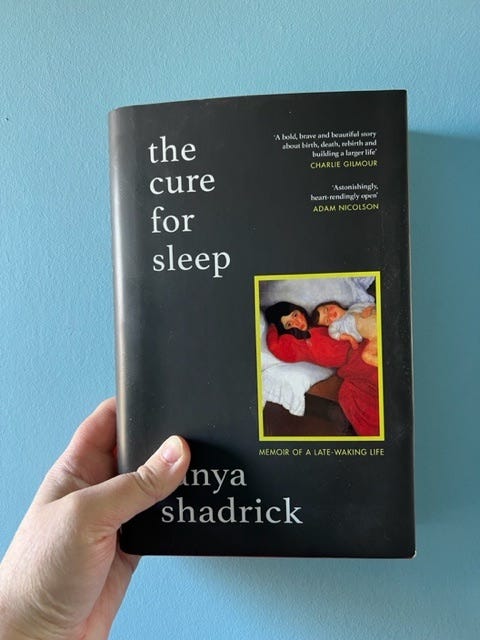

"You can’t write a book in the hope of it winning love..." Tanya Shadrick answers questions on her memoir The Cure for Sleep.

Plus, ask Helen Mort, book club news, July's writing challenge

In May the Books from the Margin book club choice was Tanya Shadrick’s The Cure for Sleep. The book chat was lively and interesting as we weighed up Tanya’s brutally honest, inspiring memoir and discussed what moved and motivated us, what made us want to know more. The Cure for Sleep, as I’m sure I have mentioned before, was one of the books that made me want to write my own book, or rather, it helped me to give myself permission to write a memoir. It helped me to find the courage in my own story, and chatting to Tanya I find that she is just as inspiring and thoughtful as the narrative voice in the book. One of the true pleasures of being in a position in which I can talk to, and share with others, authors thoughts and creative process is how much I have learned myself, as a writer, through them. I am delighted to bring you the author questions, based on the book club discussion, with heartfelt thanks for the care and consideration that Tanya has put into the answers. I hope we meet in real life soon.

1. There have been some articles recently shared in the literary community about care for memoir writers due to the very personal nature of the genre. A great deal of the Cure for Sleep is very personal, how did you look after yourself during the writing of it, and after publication?

I got the contract to write the book just before pandemic, so a month after I started work on it my children and husband were home, and my mother divorcing. There wasn’t a lot of time to think about what might come with publication. I had surges of worry, but then remembered the adage not to write about anything you won’t want to be asked about.

I can speak more usefully to choices I made nearer to publication and since then. I was clear with my editor and publicist what I would and wouldn’t do in terms of publicity…

Yes to podcasts, yes to newspapers who would interview me (but not in my home: only over the phone or outdoors) but no to first-person pieces based on extracts from the book, yes to festivals and social media engagement. Newspaper features are a wonderful boost to sales and with another type of story I’d have been glad and grateful to accept, but because my memoir is so fully about other lives as well as my own, I didn’t feel I could expose us all to the kind of very direct large-scale interest (plus below the line comments!) that comes with newspaper coverage. My advice to any first-time author is think about the risks and benefits of each type of publicity specifically in relation to you, your anxieties, your story. It’s not one size fits all.

Six months post-publication – when the main crush of events were over – that’s when I took my physical health in hand. The two years of writing the book affected me physically as well as emotionally: it’s hard to sit still for the amount of time it takes to get a book on shelves! I’ve walked daily and done light exercises every day since then and my mood is the steadiest it’s ever been. Haruki Murakami writes a lot on this – the benefits of a physical discipline for writers; so did Vonnegut and Woolf. It’s proved true for me too…

2. If Nye wrote his version of your marriage story, how would you react?

I shared this question with Nye – just as every day’s work on the book was read to him! I would have the same trust in him as he did me: that it was necessary work, and that we would discuss any difficult parts to agree something true but not unfair or unkind – this was an ethical measure we set ourselves with The Cure for Sleep. And this wasn’t just in relation to him: as I wrote, the small descriptive details or word choices that Nye baulked at when I was describing him, this led me to award the same care even to those in the book who have no concern for me, and with whom I couldn’t discuss their portrayal: my step-father, my Other Love, my father’s second family. How could I select details that gave the book meaning to the reader, while not betraying too much of those people’s lives? If Nye were writing of our marriage, and his life beyond it, that’s the kind of support I’d be hoping to give him. Not to be unkind, or gratuitous, in the words used, the details chosen.

3. Were you nervous about writing your book or were you recklessly determined? Or…neither of those? What was your overriding feeling about making your revelations?

I was both: absolutely determined – knowing that my once-in-a-lifetime opportunity had come (hence the scene towards the end of the book where I tell my mother ‘I would not be stopped’) while also experiencing waves of anxiety: Would I be sued? Would I be pilloried in local or national reviews? Or - equal and opposite - would my personal story fail to find any reviewers or readers at all?

From my conversations with other debut authors, these are common dips and swells of feeling. What helped me chart a course through them was a clarity of purpose: I knew who I was writing the book for and why. I wanted it to celebrate what I see as the heroism of daily life – those who stay when it’s difficult to do so - and I was offering it as a ration of courage to readers in that kind of life situation: carers, new mothers, single mothers, sole wage earners…

4. How did you structure your book? Or did you just dive in and organise later?

I’d never attempted a book before, and suddenly I had a contract to write one! I had the near-death as an obvious inciting incident for the first draft, but beyond that I had no structural plan – only a sense of wanting to subvert the usual life-change narrative, where the loss or crisis happens at the start and the whole book is a journey away from it. I wanted to go back before I went forward.

By the end of the second draft, I knew my writing was good – at the level of scene and sentence. I’d learned I could do that quite easily. But there was some magic missing that I’d promised my editor when she pre-empted the book – or what the book could be rather.I allowed myself one whole week to be fully stuck. I scrubbed skirting boards, dusted radiators, refolded all the clothes in our cupboards – much as I did before the arrival of my babies. Then on the very last day I’d given myself, as I carried some laundry into the bedroom… it happened. Creative grace. It really was like that. I’d read about it in Lewis Hyde’s The Gift – examples in him of other writers it had happened to like the poet Theodore Roethke with his most famous poem – and now it was given to me. It felt like that – a gift from outside. I suddenly – between one footstep and the next – saw that the book would be three lives not two, and that within them I would seen in my different roles: girl, worker, wife, mother… That idea of ‘I contain multitudes’ from Whitman, that poet who is so central to my second life in the book.

I started work the next day on the third draft without telling my editor how I was going to solve her 9-page list of concerns. I worked every day for a month and rewrote the whole book. I knew the magic was there that had been missing. The first two drafts were hard and terrible as everyone says they will be. But that third draft: my beautiful reward.5. I feel that your creativity is very much tied in to communicating on a creative level with others. Is that a fair statement? Do you ever struggle to write without that community and connection? At solitary writer’s retreats, for example.

Yes, after decades of wanting to be a writer but producing nothing, it was only when I decided to perform it - as a busker or street mime artist almost - that everything changed for me. I needed to feel open to direct, real-time exchanges with people about my stories, theirs. To show myself as an aspiring writer: to declare it. And in the two years before my first published piece, when I was trying to at least write my notes more seriously, I wrote daily in a café (after Hemingway’s example in A Moveable Feast).

I met the writer Lulah Ellender at that time – she was another mother in town trying to write her first book at a table near to mine – and also the poet John Agard, who was already a winner of the Queen’s Medal for Poetry. One day he stopped at my table and said: ‘Hey there, writer, how’s the writing coming on?’ I deprecated, said he was a writer, I was unpublished and just making diary notes… He smiled: ‘Ah, but if you keep writing by hand like that, you will be published one day.’

Those kind of moments: we can go for years on those – just being noticed by someone published in the field we hope to join. That’s why I think joining local or online writing groups like the one Wendy runs is so important in our early days.Now I have enough published stuff out in the world that I can – and do – write best completely alone in a room with no view. But when I began writing seriously my children were so young and I had no room of my own – even my laptop was shared with two under-tens who used it for their games and TV shows! So there were a few years when writing residencies – as I describe in the book – were crucial. But now I don’t need or enjoy being away from home. I write best in the house with my family nearby.

6. If you had to do it all again, both your life and the writing of the book, what would you change?

Given that regret plays a pivotal role at the start of my book (all those wasted years hiding in routine, shrinking from opportunity!) and the mistakes I make in trying to live differently after the near-death… you’d think I would want to go back and change a lot if I could. But as Nye says, everything we did and didn’t do led us to this time in our lives: we still have our quiet and rich domestic routines – as we did at the start of the book, in our twenties, but through the story of everything that’s happened since, we’re now connected to people far beyond our little house. And that was the thing we always yearned for. To feel more connected to the human family (a phrase I love in James Salter’s novel Light Years). My mistakes are what made me able to tell a story that has use to other people. And being of use makes it easier to live with those mistakes…

7. Are there any topics you felt couldn’t go in the book?

I made some clear choices up front, yes, about what could and couldn’t go in the book. My children aren’t named or described in much detail beyond their births and then a key short chapter towards the end – the only one that wasn’t read to Nye first, but to them. I don’t go into many details of the daily misery in my home once my mother remarried – partly for legal reasons (my step-father was still alive until this year), but more from a wish to have the impact of that fear stay with the reader rather than the horror of specific scenes. And my Other Love: he’s no longer in my life and regardless of how he might feel about me now, I wanted to show my huge love for him back then without revealing very much of what he said to me when he loved me too. In each case, the legal and ethical restrictions I was working to made writing the book more interesting from a formal perspective as well as making the story better for the reader. I’m a big believer in limits and boundaries in creative practice – unless one is writing oral testimony or journalism, when the full story needs to be told or every available fact presented.

[These were choices appropriate to this book, with these people in it. If I ever write another book, I will likely go through a similar decision-making process but with very different outcomes regarding style and subject matter!]

8. Do you feel your relationships have changed since the book came to life?

So many people who thought well of me in the past in one of my many other roles have been in touch or are fully back in my life as a result of reading the book. It was the most unexpected joy and the precise opposite of what I feared when publishing memoir: that I’d be challenged, attacked, ridiculed. I have letters from both my first and last teachers: how incredibly precious those are…

But… and here’s a hugely important point: You can’t write a book in the hope of it winning love and attention and apologies from those who hurt you. Perhaps that comes for a few lucky memoir writers, but it’s certainly not a thing that can motivate the writing of a book. Yuri, my Other Love, the Shadrick family… none of those people are back in my life as a result of what I’ve written.

And I set myself to that hard reality before I wrote the first word. I copied out the following from Barthes, and kept it always in view:

“To know that one does not write for the other, to know that these things I am going to write will never cause me to be loved by the one I love (the other), to know that writing compensates for nothing, sublimates nothing, that it is precisely there where you are not--this is the beginning of writing.” A Lover’s Discourse

Beyond existing relationships: it’s wonderful to meet people now that I have my story in the world. I forget what writer said this, but it’s like your soul is an open chequebook – you have secrets still of course but in essentials anyone meeting me now can find out very quickly what I stand for. I value that feeling: it frees me to focus on others, away from self. Yes, having put out a memoir of my first fifty years, I feel almost posthumous, but in a good way: a friendly ghost? No real ego needs anymore, after years of being driven by a wish to prove myself. It makes meeting new people feel very free and easy.

9. What drives you, in terms of creativity and creative response?

For my writing: the formal pursuit of finding the right lines to convey real experience as directly as I can. I work with my ear – how something sounds. Woolf wrote about this - how if you find the right rhythm, the meaning tends to follow. Amis called it ‘euphony’. And like him, I work hard so that my published work has no words or sounds that weren’t intended. I’m driven by an interest in craft, in form, and not only in story-telling.

And in all the work I do in public, as well as in what I publish? I share what I do in the hope it will call forth responses from others. This is how it is for me. How is it for you?10. You provide platforms for other creatives to tell their stories. How important do you feel it is that people do get to tell their stories?

I grew up in a time and place where too much and not enough was said, at once. Endless arguments, gossip, criticism… but silence around matters of safety, wellbeing, needs of the soul, the heart’s yearning. My higher education and my decades since of constant reading mean the world to me, but I’ve never stopped caring passionately about people who’ve never been supported to speak their feelings, let alone write about them. That’s my vocation, my purpose: to encourage others into voice, into story. Time and again – as a hospice scribe, a neighbour, a teacher, a mentor – I’ve seen how people grow when they share their first small true story. Supporting people to get that first true story out safely – that’s what motivates me.

Ask Helen Mort

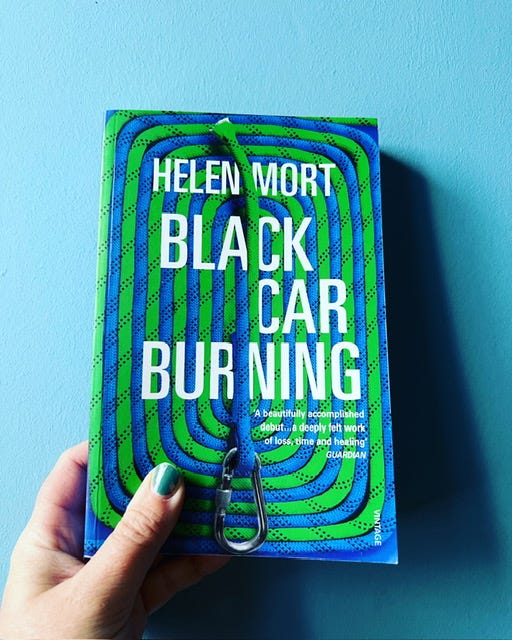

The Books from the Margin book club choice for June is Helen Mort’s wonderful novel Black Car Burning.

I’ll be sending Helen some questions to respond to next week. So if you have any questions for Helen about the book, her writing practice, writing across genres, let me know! You can book a place on the July zoom book chat which this month is on Sunday 25th 10am to 11am UK time, here:

I’m delighted that Helen will be joining us for a live zoom author chat on Friday 30th 7pm to 7.45pm UK time, here:

July Writing Challenge

My next writing challenge starts in July.

If you fancy four weeks of re-writing fairytales, come and join me for this online course. Pricing is tiered and you can book your place here:

Thanks for joining me, until next time

x

I love Tanya's work! Loved this interview!

Question regarding your writing challenge offering, what time are the zoom calls. I live in California US.

I loved this interview- Tanya is so open and honest - offers such brilliant and important advice for those embarking on memoir - thoughtful, inspirational - particularly love ‘the heroism of everyday life,’ we need to celebrate this so much more