"I was writing towards an unknown ending; wherever my body found itself, the poems would have to meet me there."

Jen Campbell answers book club questions

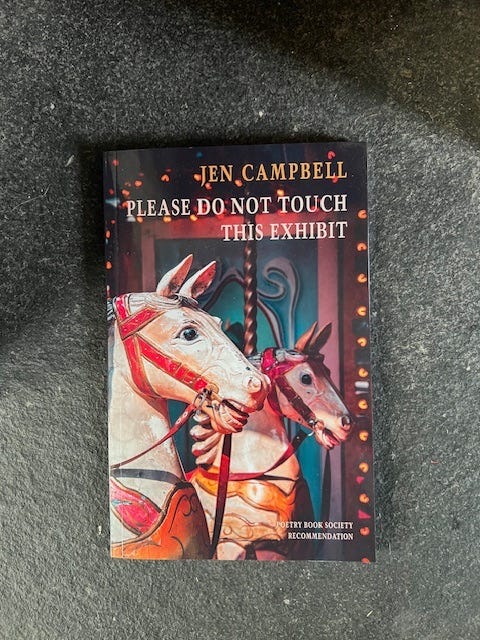

If you’ve not read Jen Campbell’s Please Do Not Touch This Exhibit, put it on your TBR pile, ask someone to buy it you for Christmas. It’s a thought provoking, superbly crafted collection in which the poet explores health trauma and IVF, loss and belonging, othering, chronic illness and disability. It’s a purposeful collection; to read it is to be taken somewhere and shown something. The poems are bold, often using metaphor to expand the exploration of self, always with attention to craft.

When the book club met to chat about it, its no surprise that there were wide ranging topics explored - health, healing, the doctor’s perspective, the patient perspective, trauma, what it means to be a woman in a health environment, craft, decision making in poetry composition. It was, I think, one of the best meet ups yet and I came away feeling energised and full of that particular joy that sharing book-love brings. Jen has very kindly given up her time to answer the book club questions with typical honesty and thought. Thank you Jen.

To what extent was writing Please Do Not Touch This Exhibit a healing process, and what was the emotional cost of writing the collection?

Perhaps it began, naively, as a kind of healing process. I started writing Please Do Not Touch This Exhibit in 2020, when it had already been several years since my first IVF appointment. As the collection progressed and I could feel the book stitching itself together, I decided to tell my editor I’d have it finished by winter 2022 (not to be unromantic but I work better when a deadline is involved). Winter 2022 would also be the end of another IVF cycle, so I knew I might be pregnant by then or I might not be. I was writing towards an unknown ending; wherever my body found itself, the poems would have to meet me there.

At the beginning this was objectively interesting. Yet, as the end date crept closer, and not only was I not pregnant but the whole process had been awful, nothing about it was interesting — and it was certainly not poetic. I’d been extremely ill with Ovarian Hyperstimulation Syndrome; 85% of our embryos had died and the doctors didn’t know why; years of pandemic and shielding were heavier than ever. How ridiculous, I thought to myself, that I’m trying to make a book out of all of this. How absurd that I am trying to craft something, that I am trying to elevate it in some way. I didn’t want to show up — to my writing desk or elsewhere. But I did because, truthfully, I didn’t know what else to do. I felt I’d signed a contract with my body; if it was trying to make something, then my mind would also try to make something. And if my body was trying so hard, it felt wrong to break my side of the bargain. So, I finished it, and I delivered it. (The painful puns are endless, aren’t they?) And, from this side, I honestly don’t know how I did that last part, but I’m glad I did.

Some of your poems utilise the white space as part of the poem. What is your process in terms of deciding on the structure and appearance of a poem on the page?

The geography of a poem is one of my favourite parts of writing, editing, and teaching poetry. What can we say with the structure of a poem, outside of the words? How can we dress it? How can we play with line breaks to create double meanings, or to make a reader stumble and question where they’ve found themselves? I enjoy playing with line length to increase or decrease the speed of a poem; using punctuation as a signpost for navigating certain landscapes. Alignment as a mimic for conversation. Prose poems as postcards or dream-Polaroids. Lists throwing themselves down a page to reflect hair falling from a scalp. The whole process intrigues me.

Your collection covers several personal, traumatic events and situations in your own life. How do you protect yourself and do you ever feel vulnerable when presenting these poems to an audience?

It’s funny, you would think that after writing twelve books I would remember that at the end of each writing process these pages are not only read by other people, but I often have to read them out to a (virtual) room full of people, too. But I do forget, or at least I block that out. Perhaps it’s necessary to do that, in the early stages at least; I might write differently otherwise. I hasten to add that this is not about dismissing the reader — quite the opposite. Considering the reader when writing is an incredibly important thing to do, especially in the editing process. Taking yourself out of the equation and imagining someone, a person with no context, peering at your words from the outside — wondering if they can make out what you mean through a window. But that reader is always abstract, always invisible. Writing is like hanging out with ghosts. Your own and other people’s. If I magicked them into something more corporeal, I think it would do a disservice to the actual, final, warm-blooded reader — and that’s no fun for anyone.

No doubt this dissociation helps when it comes to writing about traumatic events, too. I don’t exist in a vacuum but I’m very careful to only write about myself. I don’t write about my family; I don’t write about my partner. Other characters are nameless, and they flit in and out of poems. When it comes to events, there are always going to be poems that I never read aloud, subjects I will not discuss in more concrete terms. That’s why poetry is often more appealing to me than non-fiction; there’s an abstraction to duck behind. I make bargains and boundaries with myself. This makes it all feel safer, while remaining truthful.

As an add-on, I suppose there’s also an irony in that, like most disabled people, I am used to presenting myself in a certain way to doctors, to strangers. I know what it means to attempt to be heard above your body’s noise —or, rather, above society’s grumblings about bodies which dare to make noise— bringing receipts and humour as deflection, and other tools. Sometimes I find myself leaning into this when doing poetry events if I’m feeling particularly wobbly. It’s an unexpected, transposable armour.

How did you come to poetry, where was the seed planted?

Poetry is the thing I’ve written the longest. I think since I was about seven or eight. I’ve always delighted in the way poetry allows you to refract things. From a practical point of view it’s also short, therefore it’s physically easier to write — this second part being especially important as a child going through dozens of surgeries with no computer. Poetry feels like a form of evolution, too. You can morph it, surgically rearrange it. I don’t know… I’ve always felt at home in poetry.

What achievement in your life are you most proud of?

If you’d asked me this ten years ago, I would have given you an ableist response of “achieving grade 8 piano.” I pushed myself much too far to achieve that — mostly because I was praised so much for it. “Look at the girl with missing fingers and arthritis; if she can do it, anyone can!” There was definitely some circus energy lurking in the wings. It makes me wince to look back on it, and not just because it hurt so much. So, as a person who now has more compassion for myself, I’m quite proud to have left that behind. As for writing achievements, I think winning an Eric Gregory Award remains my favourite. I won’t forget the warm feeling I got when I opened that letter. It felt very special.

How did you come to the repeating motif of the house in the collection?

I remember Andrew McMillan responding to a reader question on Instagram stories. I’m going to have to paraphrase, but the question he’d been asked was ‘how do you know when a book is finished?’ And Andrew said something along the lines of finding it helpful to think of a book like a house. How, if you’ve opened every door, explored every room, mapped out every floor, you’re probably done. I adored that image. My partner and I were also moving home at the time, and I was struck by the weird similarities between viewing properties and attending doctors’ appointments. Here we were, turning up to look at houses, comparing notes, looking for problems, determining how we could ‘fix’ things, and feeling ill-equipped to make such life-changing decisions based on five-minute interactions. That felt laughably familiar. Then there’s the dichotomy between home life and hospital life, the domestic and the medical, a border I’ve been crossing and recrossing all my life. Over time, I suppose all of these things morphed together, and the house-as-body poems came to be.

Who are your go to poets, and what five collections of poetry would you recommend that respond creatively to themes of disability, othering, illness and/or belonging?

Oh gosh, there are so many. General recommendations: Thinking With Trees by Jason Allen-Paisant, How to Wash a Heart by Bhanu Kapil, Why God is a Woman by Nin Andrews, Magnolia by Nina Mingya Powles, Honorifics by Cynthia Miller. As for disability/illness/body specifically, to shout out just a few: Stairs and Whispers anthology, The Perseverance by Raymond Antrobus, Where I’d Watch Plastic Trees Not Grow by Hannah Hodgson, Hiding to Nothing by Anita Pati, Much With Body by Polly Atkin. I have a lot of poetry reviews over on my Youtube channel, along with more disability book recommendations, and general book chat, if that happens to be of interest.

Find out more about Please Do Not Touch This Exhibit Here: Bloodaxe

Books from the Margin Book Club Choice for December - On Gallows Down - Nicola Chester

The book club choice for December is Nicola Chester’s On Gallows Down. Come along to the book club book chat on 17th December 10-11am. This event is FREE TO PAID SUBSCRIBERS but I ask for a small donation from guests. You don’t have to have read the book, our book club discussions are wide ranging and exciting. It’s a great way to nourish your book-is soul!

Book your place here:

New Course Klaxon!

What To Look For in Winter

What can we learn from nature in winter? How can we write about it? Where do we exist in the natural world and how do we tie that world to our own lived experiences, physical and emotional?

Winter is the dark time when the world is waiting: a time for survival, a time for for reflection, a time to experience the darker side of the world and to dig in and recognise the strengths in ourselves and the resilience of the world around us. In this four or six week course (depending on the tier you choose) we’ll be exploring nature in poetry and prose using natural and supernatural themes. From migrant birds arriving and leaving, to insects in their subterranean hideouts, the trees speaking to each other out of sight to the rites and folklore around the darkest days. This is your chance to explore the natural winter world both as an observer and in the context of your place in it. In What to Look for in Winter we’ll explore this world through published works, museum artefacts, film, imagery and physical interaction with nature, using prompts and directed activities to write ourselves into the winter months.

The course starts on 3rd January, a chance for you to start the year by prioritising your writing, perhaps, and to face the post new year’s slump with positivity and courage.

If you are a paid subscriber to Notes from the Margin, you are entitled to a discount on the course, as a thank you for supporting me and my writing.

You can find out more about the course, and book your place on it, here:

I haven't read Jen's book (yet) but I did discover her YouTube channel recently and have been hoovering up book reviews ever since.

Haven't read the book (yet) but very much enjoyed Jen's answers to questions on this post. And it's a reminder to myself to go to her You Tube channel more often.