Ghost Lake Rising: My Dad's Last Days Spent Dreaming of the Family Farm

The Route to Ancestry is an Instinct

Quick Links

Everything on offer for paid subscribers Here.

Buy my nature-landscape memoir The Ghost Lake Here.

Buy my latest poetry collection, Blackbird Singing at DuskHere.

Welcome to Ghost lake Rising - a series of posts in which I expand and explore further parts of my memoir. They have their own section on Notes from the Margin, which you can find Here.

This week I took a trip to the North Yorkshire Archives in Northallerton, as part of the research for a new book I’m working on. I took my mum with me so that she could spend the day visiting her sisters in Thirsk, while I sank into the 16th and 17th century documents captured on miles and miles of microfilm, just up the road. (Heaven).

The route from Seamer to Thirsk feels like it is a part of my family’s narrative; a part of the stories we tell each other at family get togethers, so well-worn is the route, to us. Sutton bank, place of family legends: where our shitty old cars and vans and campers often didn’t make the incline on the way back up from the town. Where we would wait, red checked, being sworn at by other drivers, for an uncle to come and pull us up the rest of the way. The prayers for the brakes to work when we got stopped. The oftentimes when they were simply not good enough, because the cars of my childhood were rust buckets; cars at the end of their lives, bought by my dad because he could sort-of fix them and eek a few months of life out of them. Because that’s what we could afford. Place where the wardrobe my dad was bringing back from one sister or another swung straight off the roof of the car and smashed on the ground on the incline. My dad, never averse to risk or embarrassment. The fan belt that broke at the top once, my mother taking her tights off to replace it. My dad, always with a roll-up at the edge of his lip, head in an engine trying to bring some engine piece back from the dead. We were always saving things and rescuing things and bringing things back from the dead in my family.

And the landscape itself, our ties to family, how we could stand on the crest of Sutton Bank and look down to the patchwork of fields below and point out family history - Kilburn and our mouseman uncles, Sowerby and the family farm. Thirsk, full to the brim with my mother’s five sisters, two brothers, the uncountable cousins, my dad’s four sisters, more cousins. My dad’s aunty’s farmhouse on the bank itself; the family parties there, the dark of a rural night, the spark of a secret cigarette shared with cousins as we watched the car lights snake slowly down the drop.

When I took the route again this week, it felt familiar, comforting, even. When we hit Sutton Bank though, low clouds dropping, dropping, dropping until the water became rain and the mist became a blanket fog and then an accident. High-Vis vests emerging out of the grey, on this most accident-prone of steep hill drops. The road closed, the diversion we all dread - a secondary road down Sutton Bank, a road only the width of a single car, but on which cars come both ways. A steep drop down the side, no passing places, thickest of thick fogs. Memories of navigating this route before, my dad driving while we clung to the door handles in the back. Then light, then safety, the road opening up to the most green of trees, the green-gold of ripening barley, swifts, kites, hare in the road. A kind of home.

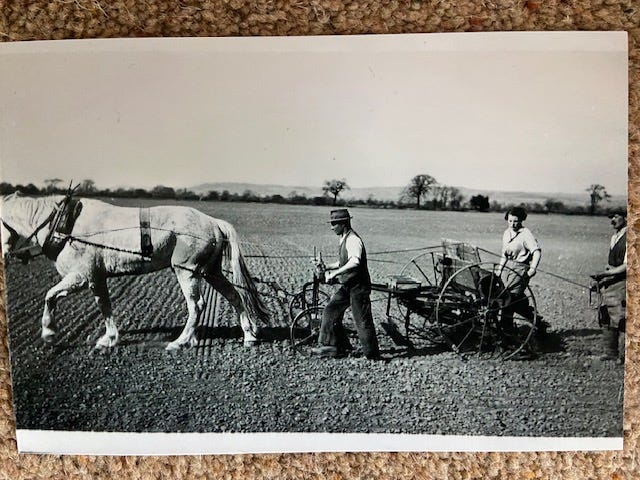

My dad will have been dead three years in August. It was his birthday last week, he’d have been 74. In the first year after his death, in the first few months after his death, while I was writing The Ghost Lake, I took a trip back to the family farm, which was never ours to own because we were tenants, not landowners, and of which I am no part, because the we in this story is the we of my father’s memory that so dominated the family narrative. My aim was to see if the farm was the same farm of my own memory. I was attempting to create my own narrative away from that of my fathers. I felt like my story had fallen away somehow after his death. I’d realised I had formed a big part of my identity on stories that were his stories, not mine. Writing The Ghost Lake was a way to find out who I actually was. I had not been to the farm since childhood, when my Nana and Grandad had left, retiring to a bungalow. In my mind’s eye the farm was an ancient place, built on the site of a medieval hospital, haunted, if you would believe my aunties. A place of ponds and chickens, and a long chalky road and a train that passed over and over like the pendulum of a clock through the fields. A place of cows and foxes and hares, of red brick barns, and cobbled courtyards. The farm in reality had not been that for many years, maybe not even in my own lifetime. When I visited I found its transformation continuing, the ancient bricked up arches and windows, hundreds of years old, now added to with new PVC doors, the house split into two labourer’s cottages, half empty. The barns gone, the pond gone, and long flat fields of early crops all round, the hum of electricity pylons over head. The same view though. The same rise of hills, rocky outcrops, low cloud.

When my dad was entering what we now know, but didn’t then, were the last months of his life, we spent much time travelling between Scarborough and Hull for chemo appointments. I’d drive, my dad would talk. The further down the cancer route we got, the more his memories returned to the family farm, the route to the town, stories of what it was to live on the land and off the land and with the land. Stories from his own childhood. He himself, though he had run a small holding of his own, had not farmed since his mid teens when he’d left the family farm to become a Rington’s tea van driver. The narrative was so strong though, the stories like tethers that brought him back; the pull to place like the magnetic forces that bring geese back to their home grounds.

When the operation that he had ran into complications, and he was intubated and unconscious and we talked to him in the hope of calling him back, it was to the land and the work that still needed to be done - the apples ripening, the chicken houses in need of fixing, the sun pooling on the stone bench next to his fish pond awaiting his return there for his morning coffee. But we couldn’t bring him back.

When I wrote about it, later, in my poetry collection, I wrote of him being called back to a childhood in which he had to bring the cows in. I created a version of him that was too busy with farm chores to leave off and return to us. My mum, when she talked of him in the beginning of that most long and dark road through grief, talked of him as the tawny owl in the field that called and called and received no answer.

I wonder if he heard us, through the fog of induced coma, if he knew we were there, holding his hands, when the life support was switched off and he drifted away from us to wherever it was. When I think of those moments now, it is as an observer. As if I was taking notes on my own life experience, ready to create this new narrative, this continuation of a family narrative so attached to place. In fact, here I am, creating the narrative of this time, shaping and re-shaping and feeling the pull of something like home, but a home that has never really been.

When we came back from Thirsk and I dropped my mum off to their small holding and my dad’s grave in the field; the grave that he had specifically asked for, and which had been a nightmare of logistics, the last crazy dad request of his life, the last risk taken, the last fuck you to any sense of normalcy, I returned with a sense of peace and with a sense of gratitude for the stories, the history I get to travel on with.

Perhaps, because I am deep in historical research, and my mind is really never in the present anymore, and won’t be until the book is finished, I am more attuned to the presence of family narrative, the stories, the history of lineage. Perhaps, as the anniversary of my dad’s death grows closer, I am more attuned to his narrative; his presence in the family, the stories that continue to be told at family gatherings like incantations to bring back the dead.

Does it matter how we categorise the pull to the past, the pull to place that would have a person re-visiting a farm she barely knew in order to feel something of her place in the family line? No. Not everything needs to be explained. Some things can just be. We are drawn to creating stories, as humans, and this is no different.

Perhaps I am making a kind of songline or dreaming track back to versions of myself that fit neat as Russian dolls in a narrative that has been passed down for years. I think I’m OK with that.

Until next time

x

My grandparents farmed in Atwick about 30 miles south of you Wendy and the first four years of my life living on their farm are the foundation of my existence. I’m trying to write a novel at the moment based on my mother‘s life in Hull during the Second World War - so family names and family stories are at the forefront of my mind at the moment. So much of what you say in this lovely piece resonates with me. Thank you.

There’s a farm in my family story as well, though none of my relatives worked the land. My parents lived in a caravan parked in a field of apple trees, in a caravan they called “The Tin House”, for a few years in the 1950s. It was the happiest time of my mother’s life and later on, when I was around and my father was long dead, it because a lost paradise, an Eden that could be revisited only in dream and memory. I’ve never quite been able to explain my intense feeling of the place being part of my identity, until now - you express it so perfectly as a songline, a place sewn into the fabric of our stories, a link trivial or unknown to everyone else, but very significant to us.