Ghost Lake Rising: Long Ago Horses

How the horses at Flixton island are like a paraffin embedded tissue slide

The News in Brief:

Everything on offer for paid subscribers Here.

Buy my nature-landscape memoir The Ghost Lake Here.

Buy my latest poetry collection, Blackbird Singing at DuskHere.

Welcome to Ghost lake Rising - a series of posts in which I expand and explore further parts of my memoir. They have their own section on Notes from the Margin, which you can find Here.

Ghost Lake Rising: Long Ago Horses

How the horses at Flixton island are like a paraffin embedded tissue slide.

A niche analogy.

When I was a microbiologist, more than ten years ago now, the lab I worked in was next door to the histology department. I am fascinated by the way biopsies are prepared for microscopic examination. Such precision. The embedding of the sample in wax, the turning of the microtome, the precision blade cutting the sample into a tissue-thin ribbon of slices, so delicate that they can’t be picked up by hand. Instead they are floated on water, fished gently onto a glass slide. I think about this a lot: the art of science, the behind the scenes dexterity of biology, the gentle precision and hands on skill that scientists perform that the public don’t see. Biology always felt more like an art than a science to me.

This is what history can be: a moment, or a series of moments, caught in the paraffin wax block of place, the thin slices peeled away to reveal something mid growth, mid life, mid moment.

Flixton island is a slight rise in the landscape, easily missed. Years ago, at a time in my life when the loss of my daughter had ground the old me out of existence, I decided to do something I’d always wanted to do and volunteered on an archaeology dig.

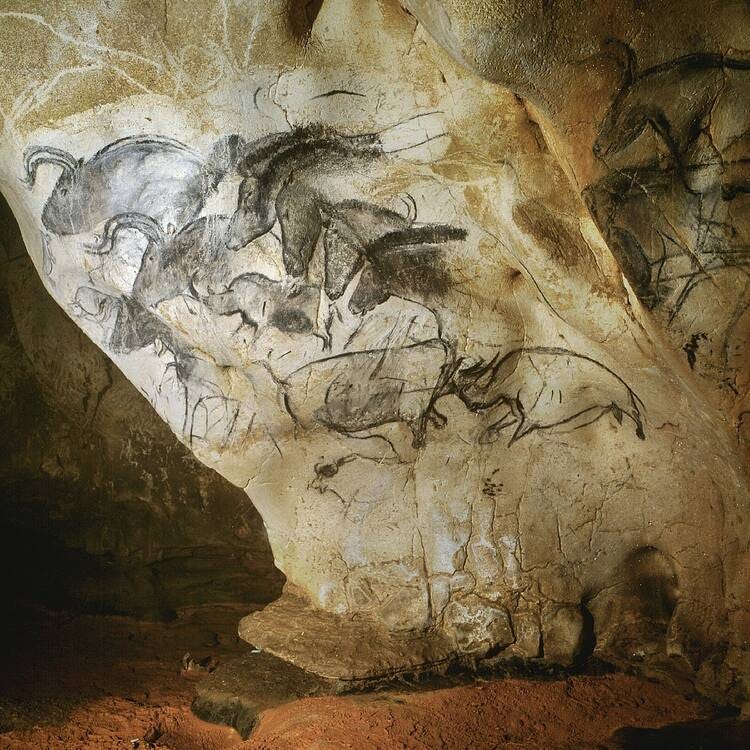

The place is fixed with many moments. 12,500 years ago, a herd of wild horses moved through a post glacial savannah to the lake here. The horses were small and stout. They were hardy and shaggy. These are the sort of horses that the people of the time painted on cave walls.

There are two stories here, two micro slices of history. One is the horse footprints at the edge of the lake, where the horses came to drink. These are the hoof prints discovered at the site while I was volunteering there. The hoof prints are crescents and scuffs and sunk-in-the-mud hoof prints clustering at a point on the lake edge. 12,500 years ago a moment is caught: it is a moment of fly bites and twitching ears and one or two heads raised, then down. It is a story of water rippling out from the point at which a soft horse lip touches the lake surface. It is a story of a heron moving past on origami legs, and of the sound of geese on the other side of the lake, and a swish of tail and crick- crick-crick of crickets, and the wind blowing through the long grass. The other story is of butchered bones placed in a pile. These too were found at the dig at the time I volunteered. The other story is also a moment fixed in time: it is a moment of wooden spears zipping through the hot air and the whites of a horse’s eyes. It is the story of the violence of horse kicks, thrashing hooves and maybe a bruise or a break of an arm or a head. The ending is of blood in the grass, horse blood, and perhaps of a warm liver being eaten raw, and definitely of meat being carried away. It is a human story. It is a horse story. How long did those moments take? Half an hour, an hour? A morning? The peaceful horses, the horses at the point of death.

The Lourdes Horse sculpture. Paleolithic.

Then a great sleep of nothingness; a great embedding of time into wax until we appear, with our tiny trowels and our weather proof macs, and the slicing of the wax begins. So delicate are the slices that we float each on the liquid surface of the human desire to know ourselves, until we can see, wet to the touch, if we would dare to touch, horse hoof prints from horses extinct for thousands of years. And bones rusted to red by the peaty ground, and a horse skull. Cut marks. The long blade people, named because of their long flint knives (held in the crook of the hand perhaps, attached to a wooden shaft perhaps), who use their knives to slice flesh, to skin the horses here. This fixed moment is one of blood-smell, flies buzzing thick as rain. Only in the still air after the horse deaths, when the group come together to efficiently butcher the animals might a person notice a cut forearm, gravel piercing the round flesh of a knee. Only then a forehead wiped of sweat. They are doubled over, skinning at the meat and I am that day, volunteering, hunched over skinning the earth and on this day standing and watching the way the wind moves the hawthorn hedge here, as the geese patter down into the river here, and the way the reeds move in the breeze, and I am watching myself, in my head, crouched low or walking by the side of the pit and pointing, look, look, you can see the way the horses move. And I am seeing, far back, but not 12,500 years back, my own smaller self, on a bike, cycling past with no knowledge of the horses here, only the scent of the nearby stables, and I am seeing another version of myself stood at a microscope, in my own kitchen, examining horse dung for worm eggs and hoping I can make a living from it after leaving my job because my daughter’s death so completely undid me. And back again, like the cranking handle of the microtome machine peeling off almost identical versions of myself, but not quite identical versions of myself, onto the water of understanding to here, this moment, this moment that is now also a part of that story, a moment in which I stand at the edge of a long extinct lake and line up the versions of myself, and the places where they touched the extinct horses of Flixton island.

Brilliant piece Wendy. Just brilliant.

Such beautiful writing Wendy. I felt I was there with the Flixton horses and with you as the times all melted into now. xx